Doubt. It means to question, to waver, to hesitate. As a noun, it suggests uncertainty, confusion, the uneasy space between knowing and not. Spelled: D-O-U-B-T. And there, lodged silently in the middle, is a letter we do not pronounce—B. Why?

We used to. Once upon a time, the B was voiced. But over the centuries, it fell silent. The word doubt comes to us from the Old French doute, which had no B at all, neither spelled nor spoken. It was only during the Renaissance, that age of classical revival and linguistic embellishment, that scholars, eager to reconnect modern words to their Latin roots, resurrected the silent letter. The Latin root, dubitare, meaning “to waver in opinion,” gave us a constellation of English words—dubious, indubitable, redoubtable—that share its DNA.

In English, two primary word families descend from this same root: doubt and double. It’s no accident that they converge on the idea of two-ness. We see it in the vocabulary: doubtful, doubtless, doublet, redouble, even doubloon.

For more in-depth look at the silent letter in DOUBT see these fun YouTube offerings by Gina Cooke:

and Rob Words:

Given this inheritance to doubt is, quite literally, to be of two minds. It is to hesitate between options, to hold competing possibilities in tension, to second-guess. Long before the French word doute entered English, there was already a native term for this condition: twogan—an Old and Middle English word whose kinship with two is unmistakable.

To be of two minds—to hesitate, to perceive one path even as you tread another—is precisely the inner tension the word doubt, with its silent and ghostly B, seeks to recover. It is not just a spelling curiosity; it’s a linguistic echo of a deeper human truth: that uncertainty is not the absence of conviction, but its companion.

Doubt and Conviction

Let me now shift registers—from language to religion. In particular, I want to consider how both Islam and Christianity might benefit from a fuller recovery of the word doubt, not as failure or betrayal, but as a necessary and even sacred companion on the path of faith.

Before turning to Christianity, I want to begin with a religious experience from another tradition entirely—one that reframes how we understand revelation itself. In The First Muslim, Lesley Hazleton’s remarkable biography of the Prophet Muhammad, she recounts what happened in the year 610, just outside Mecca, when Muhammad received his first revelation. It would become the founding moment of Islam, the point of origin for what would later be recorded as the Qur’an.

And what happened? Muhammad didn’t shout with joy. He didn’t run into the city proclaiming himself a prophet. He didn’t even speak. He doubted.

Muhammad didn’t come floating down the mountain. There were no alleluias, no choirs of angels, no golden aura. He didn’t feel like a messenger of God. According to the earliest biographers, he was terrified. He was convinced it wasn’t real—perhaps a hallucination, perhaps possession. He even contemplated throwing himself off the nearest cliff.

Muhammad trembled not with joy, but with fear. He was overwhelmed—not by certainty, but by doubt. What he encountered wasn’t confidence. It was awe. Not the casual awe of the 21st century awesome—the kind we assign to a video game or a really good slice of pizza. This was the older awe. The kind that shakes you to your bones. The kind that undoes you.

Some later conservative Islamic scholars insist we should never speak of Muhammad’s doubt. They claim he never wavered—not for a single moment. They demand, retroactively, a kind of inhuman perfection. But we have to ask—of Muhammad, and of our own tradition—what exactly is imperfect about doubt?

I would argue the opposite: doubt is not the enemy of faith but its foundation. Abolish all doubt, and what remains is not faith but heartless certainty. And certainty, when calcified into conviction, no longer seeks truth—it declares it owned. It gives rise to a brittle, self-assured dogmatism, to pride masquerading as righteousness. It becomes, in short, the posture of fundamentalism.

The irony is sharp: the word once hurled by Christian crusaders at Muslims—infidel, from the Latin infidelis, meaning “without faith”—is now used by fundamentalist Muslims to describe Christians. But true faith has always contained doubt. Not as a defect, but as an opening. A trembling space where real trust can begin.

The absolute certainty of fundamentalism is, in truth, the opposite of faith. It requires no risk, no trust, no surrender. And if this kind of absolutism is not faith, then—ironically—it is faithlessness. It is infidelity in the most literal sense. A fundamentalist, of any religion, has not discovered a deeper belief, but rather traded the vulnerability of faith for the security of control.

Like all zealots, they have no questions—only answers. They’ve built a fortress against uncertainty and mistaken it for a temple. But real faith has always lived in the wilderness: like Jacob wrestling the angel for a blessing, like Jesus fasting in silence for forty days. These are not tales of perfect clarity, but stories of perseverance, courage, and surrender.

As Paul wrote to the Philippians, “work out your salvation with fear and trembling”—not with smug certitude, not with slogans, but with reverence, humility, and awe.

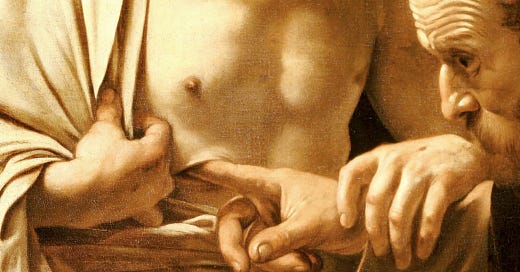

And it is that trembling—holy, honest, human—the prophet Muhammad trembling on the mountainside shares with the disciple Thomas reaching out to touch the wounds of the risen Christ. Neither floated down radiant with certainty. Both stood on the knife’s edge between presence and panic. Both hesitated. Both dared to doubt. And in that hesitation—in that very doubt—they opened a door to something truer than certainty: a faith made not of answers, but of encounter.

It is Thomas who makes the most direct and profound confession in the entire New Testament: “My Lord and my God.” No disciple articulates the full divinity of Jesus with such clarity. And yet, that is not how he’s remembered. Not as the first to name the risen Christ in such explicit terms. No, he is remembered by a nickname—a diminishment, really: Doubting Thomas. As if doubt were disqualifying. As if his need to touch the wounds somehow marked him as weaker than the others, rather than more honest, more human. But perhaps it is precisely because of his doubt that he was able to see more clearly. Because he lingered in the tension, he arrived at the truth.

Many printed Bibles include headings, brief titles inserted between sections to summarize what follows. These editorial additions can make navigation easier, but they are not part of the original text. They are extra-canonical, added centuries later by editors, not evangelists.

The opposite of faith isn’t doubt; the opposite of faith is fear.

In the Gospel of John, just before the final chapter, you’re likely to come across one of these headings: “Doubting Thomas.” And with it, the story is subtly tipped. The title preloads the scene with suspicion, casting Thomas as the skeptic, the outlier, the one who just couldn’t believe. But that framing does him a disservice. Thomas gets a bad rap. And in the spirit of stealing back the word doubt from the margins, from the misread, from the maligned, I’ll tell you why.

Let me begin a few chapters earlier in the Gospel of John. Thomas is not, as tradition sometimes paints him, a man of shaky conviction. In fact, when Jesus announces his intention to return to Bethany—a place where he had narrowly escaped being stoned—Thomas is the one who speaks up. “Let us also go, that we may die with him,” he says to the others. It’s a stark line, yes. Even a little bleak. But hardly the voice of a faithless man. If anything, it’s the voice of a realist, willing to follow Jesus into danger, even death.

That same clarity of conviction makes the events of Jesus’ final week all the more disorienting. The disciples are swept into a storm: the joyous procession into Jerusalem, the tables overturned in the Temple, a last meal shared in a borrowed room, the arrest under cover of night, the mob, the denials, the scourging, the crucifixion. It is not just Jesus being broken open, it is their entire framework for understanding who he was, and what it meant to follow him.

The disciples’ world has been turned upside down. Their teacher, rabbi, friend, and Lord, has been crucified. One of them has betrayed him and taken his own life. Another has denied even knowing him. The movement they gave their lives to now lies in ruins. It has been a devastating week.

On Sunday, they gather behind locked doors, huddled in fear. And it is there, into that anxiety and grief, that Jesus appears. He shows them his wounds—his hands and side—and then does something astonishing: he breathes on them the Holy Spirit. And with that breath, he sends them out of their fear. “As the Father has sent me,” he says, “so I send you.”

When Thomas returns, the others greet him with breathless joy:

“Thomas, the Lord is risen! He came to us! We saw him with our own eyes. He showed us his wounds. He breathed the Holy Spirit upon us, and sent us out, just as he was sent. We have been commissioned by the risen Christ to carry this message, to share this life.”

I imagine Thomas’s dubious and slightly sarcastic reply: “Oh really? Then why are you still here huddled in the dark, behind locked doors, paralyzed by fear? You say you’ve seen the risen Christ, that he’s breathed new life into you and sent you out into the world. But you don’t look like people who’ve encountered resurrection. You look terrified. You look unchanged. So forgive me if I need to see for myself. Because if this is what belief looks like, I’m not convinced.”

And where are they the next time Jesus shows up? The Gospel makes it clear: “A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them.” Still locked in. Still hiding. Still afraid. Despite having seen the risen Christ, they’ve turned out the lights, dead-bolted the doors and barricaded themselves inside.

No wonder Thomas doesn’t believe. Would you?

The worst witness possible

He gets branded as “Doubting Thomas,” but maybe it’s the other disciples who deserve the moniker. This story could just as easily be titled “The Fearful Disciples” or “The Original Frozen Chosen.”

No wonder Thomas doesn’t believe. The first witnesses of the resurrection are anything but convincing. They’re huddled together in fear, locked behind doors, paralyzed. These so-called eyewitnesses are living proof of nothing, zero, just empty words.

In the final chapters of John’s Gospel, the disciples are not paragons of faith—they are its antithesis. And that’s the real lesson here: the opposite of faith isn’t doubt; the opposite of faith is fear.

Which is why Thomas stands out. He isn’t hiding or pretending. He’s honest about what he needs. In that sense, Thomas is close kin to us—modern people in a skeptical age, wired for evidence and wary of secondhand truths. I mean, I relate to Thomas. He’s the patron saint of those who approach faith with both reverence and reason. He wants to touch the truth for himself.

In this way, Thomas approaches religion critically. But Thomas was not an unbeliever. I don’t think he decided that perhaps the chief priests, or Herod, or Pilate had been right after all. His critical instinct didn’t sever his faith, it sharpened his desire to encounter the risen Christ firsthand.

Christians are often tempted by two false alternatives. On one side is a brittle faith that leaves no room for doubt. A faith so impatient with honest questioning that it would cast Thomas aside for asking what others dare not voice. On the other side is a rigid absolutism that demands only certainty, accepting nothing that cannot be proved, touched, or tested. But Thomas offers us a better way.

For many years, there was a prayer in the Book of Common Prayer by another Thomas, Thomas Cranmer, who understood the spiritual fruit of doubt. The old collect for St. Thomas’s Day began with this remarkable line: “Almighty and everliving God, who, for the greater confirmation of the faith, didst suffer thy holy Apostle Thomas to be doubtful…”

Doubt is seen by Cramner as the “greater confirmation of the faith.” Doubts, in Cramner’s telling are part and parcel of the faith process, not antithetical to it.

It is not easy to express doubts today. All to often, such critical expressions are misrepresented. After the tsunami disaster in South East Asia, Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams wrote “Every single random, accidental death is something that should upset a faith bound up in comfort and ready answers. Faced with the paralysing magnitude of a disaster like this, we naturally feel more deeply outraged - and also more deeply helpless."

He was giving voice to something many of us feel. And yet, the next day, The Daily Telegraph headline screamed: “Archbishop of Canterbury Questions God’s Existence.”

The church, I think, has done to Thomas what the press did to the Archbishop—reduced a moment of honest wrestling into a scandal of disloyalty. Thomas is not dismissive of faith; he’s skeptical of the messengers. The disciples, after all, claim to have seen the risen Christ yet remain locked away, paralyzed by fear. Is it any wonder he doubts?

I sometimes wonder how many people peer into our churches and see something similar: beautiful music, sincere prayers, centuries of tradition all pointing to resurrection —and very little to suggest we have actually embraced an Easter reality or understand our inheritance as people who have been sent out for the world.

The silent B in doubt is more than a linguistic curiosity—it’s a remnant. A leftover from an earlier age, yes, but also a quiet witness to something deeper- a theological remnant. It reminds us that doubt has always been part of the story of faith. That to believe is often to be of two minds. We want to follow… and we hesitate. We want to trust… and we tremble.

But if we treat faith as the opposite of doubt, we turn belief into a purity test dividing the faithful from the flawed, the saints from the skeptics. But the Gospel doesn’t do that. It doesn’t say, “Do not doubt.” What it says, again and again—from Moses before the Red Sea to Daniel in the lions’ den, from Mary startled by an angel to shepherds trembling in the fields, from Jesus greeting the women at the tomb—is this:

Do not be afraid.

It is not doubt that is faith’s opposite—it is fear. Real faith isn’t about being sure. It’s about being brave.

Jesus says, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.” That blessing isn’t a scolding—it’s a calling. A challenge and a charge for today’s disciples: not to remain hidden or hesitant, but to live with conviction and openness. To live in such a way that—even while holding space for doubt—we never cease to bear radiant witness to the light of Christ.

So to the questioners, the skeptics, the seekers, and the strugglers: It’s alright to doubt.

The world doesn’t need our certainty, it needs our courage.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT!