Faith: so many different ways to describe it and such a loaded word to recover I have broken this into Parts I and II released Sunday and Monday.

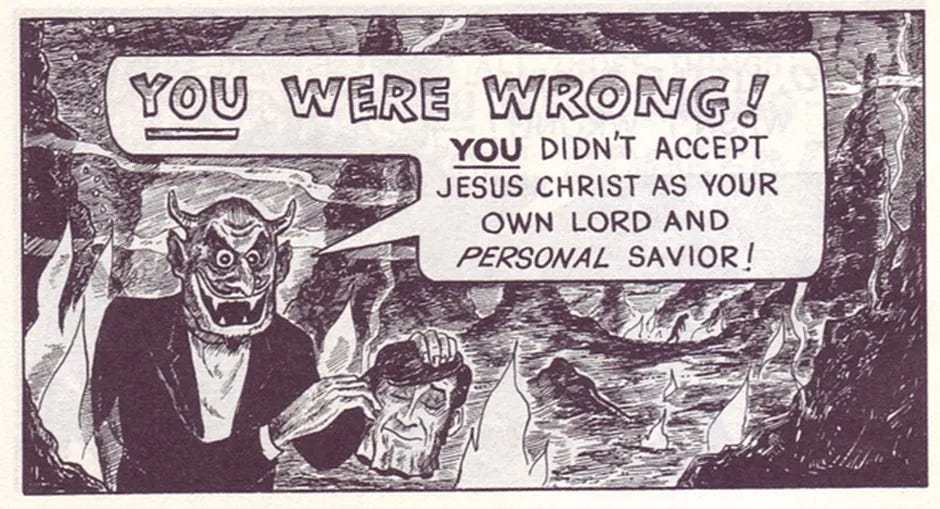

Recently, in the hushed stacks of Tulane’s library, I cracked open a theology text and a palm-sized comic fluttered to the floor. It was a Chick tract—the cartoon pamphlet you can still order by the hundred on Amazon, the size of a business card, perfect for leaving in a bathroom stall or slipping into a stranger’s mailbox.

If you’re unfamiliar, here’s the basic message of a Chick tract, repeated in some variation across hundreds of editions: “If you died tonight, do you know where you’d go? Heaven or Hell?”

The reader is quickly walked through a sequence of doctrinal propositions—Jesus died for your sins, was buried, rose again—and then urged to respond with a single act:

“Believe in Jesus. Invite Him into your heart. Make Him your personal Savior.”

This kind of faith—personal, internal, propositional—is familiar. It echoes in altar calls and youth group retreats, in bumper stickers and billboards. It is not without power. For many, it has sparked real transformation. I’m not here to mock that. I’m here to ask: Is this ultimately what we mean by faith.

Because something gets lost when faith is reduced to a moment, a mental decision, or a verbal formula. There is no story in these tracts, no example, no apprenticeship. Just the proposition: believe—and be saved.

This essay aims to place that modern, individualized model beside a thicker, more communal current that pulsed through the early church—not as some golden-age nostalgia, but as a necessary recalibration. I want to steal the word faith back—to recover its biblical heft as lived trust, public allegiance, and shared fidelity to a kingdom that subverts empire and reorders everything.

FAITH = I Am Persuaded

The Greek word most often translated as faith in the New Testament is πίστις (pistis)—a word that, in its original context, didn’t primarily mean belief in a set of doctrines. It came from the world of rhetoric and persuasion. In ancient Greek oratory, to have pistis was to be persuaded. A skilled speaker didn’t simply deliver facts; they moved their audience, shifted minds, stirred hearts, and forged allegiance. To say someone had pistis meant, quite literally, “I have been convinced.” Or more fittingly: “I am persuaded.”

This opens up a deeper and more dynamic reading of the New Testament. When Paul talks about pistis Iēsou Christou—the faith of or in Jesus Christ—he’s not describing a static intellectual assent. He’s describing a radical reorientation, a life turned inside out. It’s like being knocked off your horse—heart and mind convinced, compelled, and drawn toward trust and loyalty in Jesus. It’s less like checking a doctrinal box and more like staking your life on a new allegiance.

In this light, faith isn’t something you merely hold; it’s something that holds you. It’s not a personal possession—it’s a public persuasion.

This rhetorical background helps explain why pistis had such social and political force. In the ancient world, to be persuaded by a message meant more than agreement—it meant alignment. You didn’t just nod in approval; you took a side. So when early Christians declared their pistis in Christ, they weren’t just making a theological claim. They were pledging their lives to a countercultural way of being—one that stood in contrast to empire, hierarchy, and domination.

Over time, our English word faith has been tamed. It’s become a soft word—personal, interior, abstract. But in the biblical imagination, pistis is anything but passive. It’s active, embodied, and communal. It changes how you live—and to whom you belong.

To say “I have faith,” in the biblical sense, is to say: I am persuaded. I am convinced. I belong—not merely to myself, but to Christ, to his people, and to his way.

Faith as Vision: Seeing with New Eyes

In The Heart of Christianity, Marcus Borg offers what he calls an anatomy of faith. He begins with the version most of us inherited and rarely question: faith as assensus—the idea that faith is chiefly mental assent to doctrinal statements. Recite the creed, sign the belief statement, and you’re in. Useful as far as it goes, Borg says, but woefully thin.

Take the Nicene Creed. “Begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father.” I believe it. On a good day, I can even explain it. But I struggle to see how it helps me raise my kids, love my neighbor, or face my inbox on a Tuesday. It’s a soaring claim about Christ’s divinity, but it often feels like it’s orbiting somewhere far above my actual life.

So Borg proposes three older, thicker alternatives, drawn from the biblical tradition, classical Latin vocabulary, and modern theological reflection.

Fidelitas — Loyalty. Faith as steadfast allegiance to Jesus and his way, even when the empire demands another pledge. It’s less “I believe this about Christ” and more “I won’t bow to Caesar.”

Fiducia — Radical Trust. Faith as leaning the weight of your life on God’s goodness—releasing the need for guarantees, metrics, or control. It’s courage without certainty.

Visio — A Way of Seeing the World.

This one is my favorite, because everything else flows from how you see—yourself, your neighbor, the world. Faith begins not as doctrine but as imagination. It starts when we begin to envision the kingdom of God, practiced and embodied in the community of Jesus.

A wonderful analogy from The Wizard of Oz. The Wizard lives in the Emerald City and you couldn’t be faulted for assuming that the city was named for the fact that it was, in fact green. But in L. Frank Baum’s original book, the city isn’t green at all. It’s called the Emerald City because, upon entering, visitors are required to wear green-tinted glasses—literally locked onto their heads by the gatekeeper. Through those lenses, everything appears, you guessed it, emerald. The color isn’t in the city. It’s in the glasses. The point? The lenses you look through determine your view, your perception of the world.

Faith, rather than creedal assertion, should work the same way. Our social, theological, and economic lenses shape what we see—and what we ignore. And most of us are handed glasses ground not by Christ, but by empire.

So ask yourself:

What kind of glasses were you given—and who gave them to you?

Do you see others as beloved, or as burdens and threats?

Are you looking through the eyes of Jesus—or through the goggles of profit, nationalism, or fear?

What do your lenses train you to overlook?

Have you been taught to see people as image-bearers—or as problems to be solved, disconnected from you, to be locked up, deported, or left on the street because they “made their choice”?

Clearly, Jesus sees through a different set of lenses.

He calls the poor “blessed,” the peacemakers “children of God,” the last “first.” His vision is upside-down—or perhaps right-side-up—while ours remains inverted. And his witness to that reality, the witness of Scripture itself, is a drumbeat we too often fail to hear.

Scripture’s Drumbeat

If we let Scripture speak on its own terms—without filtering it through centuries of doctrinal shorthand or altar-call theology—it becomes unmistakably clear: faith is not something you think. It’s something you do. Over and over, the biblical witness ties faith to embodied action, to concrete response, to a way of being in the world that makes trust visible: (Feel free to skip the plethora of scripture is you are already convinced. TL;DR at bottom)

James 2:17

So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.

James doesn’t ontrast faith and works. He says faith without works isn’t faith at all.

Matthew 7:21 Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord,” will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven.

Saying the right words isn’t enough. Faith is obedience.

Micah 6:8

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?

Not “to think rightly,” but to live rightly.

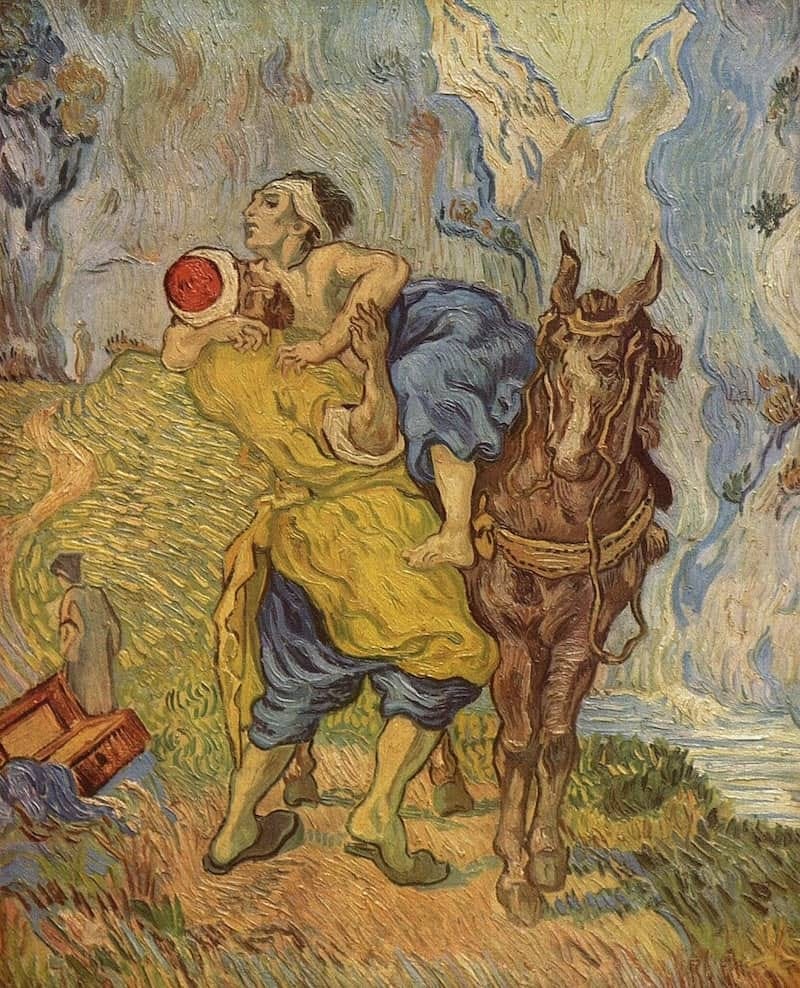

Matthew 25

For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me…

“Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.”

The sheep and the goats aren’t divided by theology, but by action. The ones who practiced love are called righteous—not because they recited the correct creed, but because they showed up.

Luke 6:46–48

Why do you call me “Lord, Lord,” and do not do what I tell you? I will show you what someone is like who comes to me, hears my words, and acts on them. That one is like a man building a house, who dug deeply and laid the foundation on rock…

Faith isn’t lip service; it’s structural integrity.

Isaiah 58:6–7

Is not this the fast that I choose:

to loose the bonds of injustice,

to undo the thongs of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

Is it not to share your bread with the hungry,

and bring the homeless poor into your house…?

Right worship isn’t about ritual precision but social transformation.

John 13:35

By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.

Not by doctrinal correctness, but by embodied compassion.

1 John 3:17–18

How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help? Little children, let us love, not in word or speech, but in truth and action.

The proof of faith is generosity, not rhetoric.

Amos 5:21–24

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies…

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

God rejects performative religion in favor of real-world justice.

Galatians 5:6

For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything; the only thing that counts is faith working through love.

That line should be etched into the church’s foundation stone. Faith working through love.

TL;DR

Matthew 21:28–31

Jesus himself tells a story to drive this point home. A father asks two sons to go work in his vineyard. One says, “I will not,” but later goes. The other says, “I go, sir,” but never lifts a finger. “Which of the two did the will of his father?” Jesus asks.

Scholars often cite this passage as evidence that discipleship involves praxis. But they rarely frame it within the deeper clash Jesus is naming: between communities that profess allegiance to God while comfortably conforming to empire, and those that may stumble or hesitate, but ultimately live out the values of the kingdom.

The contrast is not just between belief and unbelief—it’s between verbal piety and embodied trust, between religious or liturgical performance and actual participation in God’s justice.

If we’re going to recover what faith means, we have to remember: Jesus doesn’t call people to orthodoxy, or to believe the right things… He calls people to follow him, to see the world through Christ-tinted lenses and to self-sacrificially love one another as he loved us. We can continue arguing or struggling with orthodoxy even as we work in the God’s field.

Part II How Faith Became a System published tomorrow.