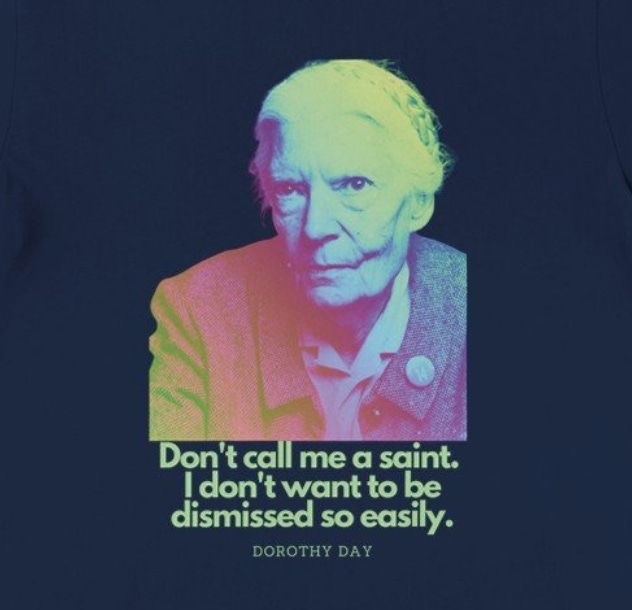

Dorothy Day was a badass! Agitator. Troublemaker. Saint?!

If the word saint conjures only stained glass, halos and serene piety, let me introduce you to Dorothy Day. She didn’t glide through history in robes of virtue. She disrupted it—in scuffed shoes and protest lines, in soup kitchens and jail cells. Her life wasn’t a retreat from the world’s mess but a full-bodied plunge into it. She refused to pay taxes. Didn’t salute the flag. Never voted. Was arrested more than once for protesting war and injustice. She once called bishops “sharks” and accused the Church of abandoning its own teachings. She ran away from home, struggled with depression, attempted suicide, and by all accounts had a mean temper. And still—she founded a movement.

She co-founded The Catholic Worker Movement in 1933. What began as a newspaper she edited quickly grew into a network of houses of hospitality offering food, shelter, and dignity to those the world deemed expendable. Dozens of volunteers lived and worked alongside her—thousands more followed. It wasn’t just a charity she created—it was community.

She could be acerbic. Impatient. Blunt to the point of bruising. She was quick to criticize bishops, quick to call out hypocrisy, and even quicker to snap when sentimentalized. When someone asked her for her soup recipe, she said, “You cut the vegetables until your fingers bleed.” When a critic accused her of being too hot-headed, she fired back, “I hold more temper in one minute than you will hold in your entire life.” But her most enduring line came when a journalist called her a saint. “Don’t call me a saint,” she said. “I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.”

For a great article on Day Dorothy Day: A Saint for Our Age? By Jim Forest

Saint-Making: The Institutional Process

Ironically—despite her protests—Dorothy Day is now on the path to canonization. The Roman Catholic Church has a formal, multi-stage process for declaring someone a saint: a carefully regulated journey managed by church authorities, theologians, and Vatican officials. It begins with the title “Servant of God,” advances to “Venerable,” then “Blessed,” and finally—if the candidate has two verified miracles—“Saint.” The process is meticulous. Documented. Discerned by committee. In other words, sainthood is no longer recognized by the community; it’s conferred by the institution.

Sainthood, as officially defined, is also something that happens only after death—and only for those deemed exceptional moral exemplars. According to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Saints are persons in heaven (officially canonized or not), who lived heroically virtuous lives, offered their life for others, or were martyred for the faith, and who are worthy of imitation.” It’s a noble vision. But one that turns sainthood into a distant, posthumous reward.

There is nothing overtly wrong with this definition. But when sainthood becomes a posthumous honorific—awarded only after heroic virtue and miraculous evidence—it drifts far from how the term was used in Scripture. Saints become more venerated than emulated: lifted onto pedestals, removed from the grit of real life, and transformed into objects of awe rather than patterns to follow. In this model, sainthood is granted not for faithful struggle, but for spotless legacy. Often, only once the mess has been cleaned up. And sometimes—quite literally—once the body has been taken apart.

During my time at Oxford, I remember when the thigh and foot bone of St. Thérèse of Lisieux— a French Carmelite nun who died at age 24—toured through town in a fancy reliquary. Some rolled their eyes. Others lined up to touch the casket and whisper prayers. There was little discussion of her daily life, her convictions, her discipline of love—only reverence for the relic. Even my alma mater, Sewanee, keeps a piece of St. Thomas Aquinas’s finger sealed in a reliquary beneath the chapel altar.

Martin Luther loathed this kind of sainthood. In his Wittenberg, Prince Frederick the Wise had amassed an extraordinary collection of sacred relics—everything from a tooth of Saint Jerome to three pieces of Mary’s cloak, a strand of Jesus’s beard, even a piece of bread from the Last Supper. One display claimed to contain a twig from Moses’ burning bush and a feather from the wing of the angel Gabriel. It made Luther’s blood boil. “How does it happen,” he asked, “that eighteen apostles are buried in Germany when Christ had only twelve?”

Is this what we mean by holy? Surely not.

Etymology- ‘Holy’ and ‘Saint’ Are the Same Word

To reclaim the word saint, we have to begin with language. In both Greek and Hebrew, the words translated as saint and holy come from the same root. There is no hierarchy between them—no moral promotion, no spiritual upgrade. Linguistically and theologically, they are the same word. The same calling.

In Greek, the word is hagios (plural: hagioi). It means “set apart”—not morally superior, not mystically radiant. Just… set aside for a purpose. It’s the word the New Testament uses interchangeably for holy ones and saints. No distinction. No separate categories. To be holy was to belong—to a different story, a different kingdom, a different way of being in the world.

In Hebrew, the word is qadowsh, meaning “to cut” or “to sever.” The image is almost surgical. Holiness wasn’t about climbing a moral ladder—it was about being sliced away from the ordinary, consecrated to something deeper. A tool, a bowl, a priest, a people: all could be qadowsh if they were claimed for God’s purpose. To be holy was to be committed—not to status, but to service.

Isaiah hears the seraphim cry, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts” (Isaiah 6:3)—not to suggest God’s distance, but God’s difference. Revelation echoes the same phrase (4:8), placing this radical holiness at the very center of the divine.

But over time, that difference was misunderstood. Holiness came to mean untouchable, unrelatable—reserved for the rarefied few. And sainthood followed. What was once a communal, incarnational calling became a posthumous pedestal.

To recover the biblical vocabulary is to remember: holy does not mean flawless. Saint does not mean dead. Both mean set apart—for love, for justice, for mercy. Not someday. Not somewhere else. But here. And now. People are often surprised to discover how freely—and how communally—the New Testament uses the word saint.

What ‘Saint’ Originally Meant

In Paul’s letters, the word saints appears over 40 times. Always plural. Always present tense. It’s not an honorific. It’s not reserved for the morally elite. And it’s certainly not posthumous. For Paul, saint means you all, here and now, in Christ.

Let’s break that down:

First, saints is always plural. Paul never writes to an individual saint, never lifts one person above the rest. He addresses communities—to all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi (Philippians 1:1). The term isn’t about personal elevation; it’s about shared identity. You can’t be a saint alone.

Paul, for example, addressed his letters to all the saints in Rome, Corinth, Ephesus, and Philippi. It’s important to see that he wasn’t writing to the morally elite or the spiritually impressive. He was writing to the whole church—including the doubters, the strugglers, the people still figuring it out. Sainthood wasn’t reserved for the few. It was the calling of the many, together.

Second, Paul never uses saint in an institutional or canonized sense. There’s no official process. No ecclesiastical seal of approval. The word isn’t bestowed by a hierarchy—it’s embraced by a community already trying, failing, forgiving, and following Christ together.

Third, the term is never used after someone dies. There are no posthumous saints in Paul’s vocabulary. To be holy is to be alive—a living sacrifice, as he puts it in Romans 12:1. Holiness is not a retrospective label; it’s a present-tense calling.

Fourth, saints are not described as morally exceptional. Paul calls deeply flawed communities saints—people who argue, who fall short, who misunderstand the gospel more often than not. Their sainthood doesn’t come from their success; it comes from their belonging. It’s not about personal perfection—it’s about relational participation in Christ.

Take the Philippians, for example. Their church wasn’t without tension. Paul urges them to be of the same mind, warns against selfish ambition, and cautions them about distorted teachings. Even amid relational conflict, ideological division, external threats, and false teaching, Paul still calls them saints. He opens his letter: “To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi” (Philippians 1:1). Not because they’ve achieved moral excellence, but because they belong to Christ—together, in real time, in real struggle.

Fifth, and finally: for Paul, a saint equals you (plural) + here and now + in Christ. That’s the formula. It doesn’t mean “everyone is a saint” in a way that flattens the term—any more than everyone who owns a guitar is Jimi Hendrix. But we are all called to be saints. And that call isn’t about repeating what others have done. It’s about embodying Christ—faithfully, courageously—in your own time and place.

Because if you flip through any book of saints, official or otherwise, you’ll find no two look alike. Saints don’t copy. They incarnate. One challenges kings, another feeds the poor. One is cloistered in prayer, another is marching in the streets. What they share isn’t uniformity, but fidelity. Each one says yes to grace in a particular context, with a particular voice, under particular pressure.

That takes discernment. It takes vision. And it takes a high tolerance for ambiguity, chaos, and cost. Because sainthood isn’t about escaping the world. It’s about stepping deeper into it—bearing witness to a kingdom that doesn’t play by empire’s rules.

How the Meaning of ‘Saint’ Shifted

In the first three centuries of the Church, to be a saint was to live a life set apart from the values of the Roman Empire. The term wasn’t abstract or ceremonial—it was dangerous. Christians were persecuted, jailed, tortured, and killed. To be “holy” or “set apart” meant exactly that: separated from empire: from Caesar-worship and the Roman pantheon. From the extractive economy and the logic of domination. From a peace built by violence. From a society that rewarded the strong and discarded the weak.

In contrast, early Christians gathered at tables of shared food, not social rank. They proclaimed peace through forgiveness, not force. They cared for widows and orphans, for slaves and strangers. That was their holiness. That was their sainthood. And they paid for it in blood.

So it’s no surprise that early Christians celebrated their leaders and especially their martyrs. The word saint was inseparable from costly discipleship. Churches would gather at the tombs of martyrs, remembering them not as heroes of perfection but as witnesses to a kingdom not of this world.

But everything changed when Constantine canonized the Church. By the fourth century, with imperial sponsorship, the Church shifted—from persecuted movement to protected institution. Christians were no longer fugitives from empire; they were functionaries within it. Bishops gained political clout. Churches rose atop the tombs of martyrs like St Peters tomb.

Relics were collected, enshrined, and sometimes sold. Liturgies began to commemorate specific holy men and women. The architecture of empire began to shape not just buildings—but the moral imagination of the faithful. Saints became patrons. Saints became the names of cathedrals. Saints became venerated figures with miracle stories, feast days, and tokens for pilgrimage. In 835, Pope Gregory IV declared November 1st the universal Feast of All Saints—a theologically rich move that affirmed even the unnamed faithful deserved remembrance. But the shift didn’t stop there.

Over time, sainthood became institutionalized. It moved from a present-tense identity to a posthumous status. From a communal calling to an individual achievement. And it became controlled by the very powers the early saints had resisted. A saint was no longer simply one of the faithful. A saint was someone officially recognized by Rome, canonized through an elaborate process, and immortalized through a system of sacred commodities—bones in glass, garments in gold, faces in stained glass.

What began as a witness to Christ became, in many cases, a spectacle. The very holiness that once resisted empire had now been absorbed by it.

And yet, even in the midst of that shift, the original meaning never fully disappeared. It still flickers, still breaks through. In every community that dares to live set apart from violence, domination, and greed, there is a glimpse of the early saints. In every meal shared across boundaries, every protest for peace, every act of stubborn love in a brutal world—holiness.

So what does it mean to be holy?

In the scriptural sense, holiness is not about perfection. It’s not about isolation or superiority. It’s about reflecting the character of God—particularly God’s compassion, justice, and mercy. This is why theology matters. Because the shape of your holiness will mirror the shape of your God.

If your God is primarily defined by wrath, punishment, and power, then to be holy will mean becoming more severe, more legalistic, more controlling. If your God values wealth, strength, and order above all else, then so will your idea of sainthood. You’ll aspire to dominate, to win, to accumulate. And many have. History is full of saints—so-called—who were revered not because they looked like Christ, but because they looked like Caesar.

But if your God is the One who liberates slaves, heals the sick, touches lepers, eats with the excluded, and dies forgiving his enemies—then holiness will look very different.

To be holy, then, is to live a life that is set apart—not for its distance from the world, but for its refusal to mimic it.

It is to say no to the default arrangements of society:

No to commodified relationships.

No to hyper-individualism disguised as freedom.

No to happiness sold as a product.

No to endless accumulation.

No to power without love and grace.

Holiness is not piety withdrawn; it is loving-kindness enacted. It is the decision to arrange your life in such a way that it bears witness to something deeper, truer, more gracious than the empire’s vision of success.

Holiness is not piety withdrawn; it is loving-kindness enacted.

Because the truth is: you slowly become what you love, what you desire, what you worship. Perhaps saints just do it a little faster than the rest of us. They walk away from the logic of empire more willingly.

They risk more, hope more, lose more, forgive more—not because they’re better, but because they’re caught up in a different story.

Dorothy Day was one of them. Her life wasn’t polished, it was poured out. Her sanctity wasn’t ornamental, it was cruciform. She believed another world was possible.And she arranged her life to prove it. (Though I still wouldn’t call her a saint to her face.)

That, at its heart, is what it means to be HOLY.