In his book Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat recounts a striking conversation he had with atheist provocateur Christopher Hitchens, author of books like God is not Great, at a party in Washington, D.C., sometime in the mid‑2000s.

Hitchens: “Suppose that Jesus of Nazareth really did rise from the dead.”

Douthat (after a pause): “Okay, let’s suppose he did.”

Hitchens: “Well, then what exactly would that really prove?”

Hitchens, in this moment, wasn’t disputing whether the resurrection happened, but asking why it would matter if it did. What would it mean for such a breach of nature, or history to occur?

Douthat admits he didn’t have a ready answer. But the question stayed with him because it was serious. It cut through the usual debates about miracles or metaphors, pushing into deeper waters: If Jesus really rose from the dead, what would that change about God, about the world, about us?

This essay is an attempt to answer Hitchens’s question.

Resurrection- a supporting wall of Christian theology

Resurrection isn’t a footnote in Christian theology, it’s a load-bearing wall. Paul puts it bluntly: “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). That’s a strong claim. But what precisely are we claiming when we say it? That the event happened literally? Figuratively? Spiritually? Metaphorically? Does it reshape the cosmos? Reveal the cosmos? Or is it just Jesus pulling off one last miracle, sealed off as a singular event in the past and the further we get from it the more dilute it becomes?

Anyone familiar with my Easter preaching has likely heard the story about being identified as a priest on a train and asked, point blank: “Do you believe in the resurrection?” Read Easter Sermon here

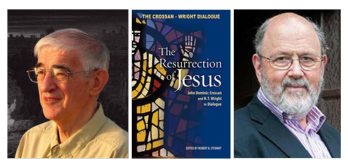

The question came because of the book I was reading at the time—The Resurrection of Jesus, a published conversation between two faithful scholars, N. T. Wright and John Dominic Crossan. Both believe in the resurrection, but they hold radically different ideas about what that means.

One of the things they share is a rejection of the common misunderstanding of resurrection as resuscitation. Jesus wasn’t revived like a patient in a medical drama whose flatline EKG suddenly leaps back into rhythm. Lazarus was resuscitated; Jesus was resurrected. The difference? Simple. Lazarus went back to work on Monday—life as usual. Jesus did not.

But there are serious differences between the two scholars. Crossan sees the resurrection as a profound theological and visionary truth but not a physical event in the ordinary or merely historical sense. It isn’t about a corpse walking out of a tomb; it’s about a people rising up in the name of the crucified. For Crossan, resurrection lives in parable, in poetry, in community memory, as a living metaphor. It transforms because it is proclaimed, not because it can be proved. Wright’s critique is that in rescuing the resurrection from modern incredulity, Crossan risks hollowing it out—turning the empty tomb into a powerful symbol, perhaps, but no longer a disruption of history. In Wright’s view, what gives the metaphor its power is that it is anchored in an event. Without that anchor, proclamation risks becoming performance.

In contrast, Wright argues that the resurrection was a bodily event located in history. It happened, he insists, “on the third day” and not as myth or metaphor, but as a singular, surprising moment when God raised Jesus body from the dead. His project is to situate the resurrection within the bounds of historical inquiry. The tomb was literally empty.

Crossan, for his part, sees Wright’s approach as leaning too heavily on history—as if what matters most is whether we can reconstruct the mechanics of the event. The result, he suggests, is a kind of forensic faith—resurrection imagined almost like a scene on surveillance footage, oddly clinical and fixated on the fate of “the body.”

This conversation between the two scholars is pretty representative of the way people try to get their head around the impossible and unimaginable.

I want to take another approach entirely and I must admit great difficulty in writing this in a way that doesn’t itself become a full length book. So here is my approach. Two part series on resurrection. Today give you the answer that matters to me and that addresses Hitchens question. This is the bedrock on which my confidence in Jesus vision of the world is built. Then tomorrow, Part II focused on the more academic rationale for why I think what I think. Keep in mind this in my studio - the place I practice, dream, invent, and what I offer here is always open to revision - it is a work in progress.

My approach is not to start talking about resurrection as though it were the mechanism by which we are forgiven for our sins, not to start talking about resurrection as a one-off but as a divine pattern that humans are slow to see because we go chasing after other gods—power, comfort, pleasure—offered to us by the promises of politics, media, society and our own self-deception and selfish proclivities. Just as true in the ancient world as in the modern.

Most theological interpretations of Jesus’ death and resurrection—including those advanced by Wright and Crossan—are grounded in a cosmological framework shaped by the Genesis narrative: a perfect garden, a primal fall, and the rupture of creation. Within this framework, resurrection is construed as a divine transaction—a supernatural remedy for a cosmic breach. Jesus, depicted as the sinless second Adam, comes to reverse the consequences wrought by the first.

But when the literalness of that cosmology no longer holds—when 21st-century people no longer imagine a physical Eden, a literal Adam and Eve, or a piece of fruit that once and forever altered the moral structure of the universe—what are we to do? I begin by asking a radical question:

What if resurrection is not a divine repair of Eden’s rupture? What if it is, instead, a revelation of what has been true since the beginning of time?

Paul’s language—“As in Adam all die, so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:22)—makes perfect sense within his cosmological framework. He writes from within a three-tiered universe, shaped by assumptions about how the world was created, and how it fell—through the disobedience of Adam. The cost of that disobedience was more than expulsion from the garden: it was the transmission of sin, original sin, to all humanity. Within this worldview, Jesus’ death and resurrection function as a restoration—recovering what was lost: humanity’s standing before God, the divine image, and access to eternal life. It is a transactional model, and one deeply embedded in the cosmology of its time.

But if we are no longer bound to that cosmology, if there are compelling alternatives, are we free to imagine something richer: not transaction, but revelation.

In this frame, resurrection is not God changing posture. It is God revealing who God has always been. It is not a supernatural correction to restore divine dignity—it is the unveiling of divine reality.

We start to see that Jesus, as the revelation of who God is, doesn’t demand sacrifice. The prophets made this plain: “Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings, I will not accept them,” says God in Amos 5:22. “The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart” (Psalm 51:17). This is at stark odds with the gods of the Bronze Age, who demanded offerings to appease their wrath or curry favor. Those gods needed something from us. But the God revealed in Jesus needs nothing. God provides. That’s what Abraham discovers on Mount Moriah—not a God who demands the sacrifice of a son, but a God who will provide the lamb. The name of that place—Yahweh Yireh means God provides. The relationship was never about exchange. It’s about revelation.

In fact, Jesus himself points to this pattern. When he speaks of Jonah in the belly of the fish, or of the temple torn down and raised in three days, he is not offering cryptic hints about his own resurrection in isolation. He is placing himself within an ancient rhythm—a pattern of death and return, descent and rising. He’s not inventing resurrection; he’s locating it. He is mapping his story onto the coordinates God has been sketching all along.

And the meaning of resurrection, far from being a new idea, deepens as the New Testament unfolds. In the Synoptic Gospels, resurrection is already a matter of sharp debate. The Sadducees reject it. The Pharisees defend it—as a future vindication, grounded in apocalyptic hope.

And in John’s Gospel, something shifts. When Martha affirms the Pharisaic view—“I know he will rise at the last day”—Jesus interrupts with something unthinkable: “I am the resurrection.” Resurrection is no longer just a future event. It becomes a person. A presence. A rupture in time, standing in front of her.

This is the heart of my claim: resurrection does not break the biblical pattern. It reveals it. This has been the logic of God all along. Resurrection is not the surprise ending to the Jesus story—it is the shape the whole story has always been about. When Jesus predicts his death and resurrection, it’s not because he possesses some supernatural foresight. It’s because he trusts the pattern already unfolding in his own Scriptures. The Hebrew Bible—the text that shaped Jesus’ imagination—is full of resurrection stories.

The early church knew this. That’s why the Easter Vigil begins in the dark—not because all is lost, but because resurrection always begins as creation did: in darkness, before light. The Vigil doesn’t simply recall past events; it enacts a pattern. It immerses the community in the deep rhythm of God’s work so that by the time the stone is rolled away, we’ve already seen the shape of resurrection many times over.

Noah, emerges from the flood not into desolation but into promise—the ark coming to rest on dry ground, a rainbow stretched across the sky in covenantal renewal. Moses leads Israelites through the Red Sea, from slavery and bondage to freedom and new creation. We hear the prophets announce the renewal of the human heart—no longer of stone, but of flesh, alive with the Spirit. We descend with Jonah into the belly of the fish, a tomb of sorts, and witness his return—not just to land, but to purpose. In Ezekiel’s vision, we see the valley of dry bones, scattered and lifeless, and they rise, upright, a living multitude. These are not merely moments of survival, nor are they moral tales. They are breadcrumbs—traces of the divine rhythm that Jesus steps into and reveals. They are resurrection stories, each one bearing witness to the shape of God’s work in the world: from death to life, from chaos to order, from despair to joy—resurrection is already pulsing through the story.

Jesus isn’t a one-off, an oddity, a pariah. (Who is that? That’s Jesus—the only one ever to be resurrected.) No. The idea that resurrection is singularly applied to Jesus as a special case isn’t biblically justified. Resurrection is everywhere.

Even though we no longer inhabit Paul’s cosmos—a three-tiered universe with heavens above, earth below, and the underworld beneath—we share something more essential with him: Paul never imagined that resurrection belonged to Jesus alone. For Paul, resurrection is not a private miracle or a singular exception but a cosmic and communal reality that reorients all of life. “It is no longer I who live,” he writes, “but Christ who lives in me” (Galatians 2:20). Resurrection is not just what happened to Jesus—it is what now happens in us: “we were buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead… so we too might walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4). And most vividly of all, Paul declares, “All of us, with unveiled faces, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (2 Corinthians 3:18). For Paul, resurrection is not a future prize—it is a present unveiling.

And now let me return to Hitchens’s question: So what?

Let’s say it really happened—that Jesus rose from the dead. What does that change?

For many Christians, the instinctive answer is that the resurrection is the mechanism by which our sins are forgiven. That Jesus paid the price. That God was satisfied. But what if resurrection isn’t a cosmic transaction at all? What if, as radical as it may sound, Jesus’ death and resurrection don’t change the structure of the universe but instead reveals what’s been true from the beginning?

What if Adam’s sin in the garden was never powerful enough to undo the goodness of creation? (And honestly, why do we assign Adam so much power?) What if the image and likeness of God in us was never revoked? What if resurrection doesn’t fix something broken—but unveils something whole? That our original blessing: God’s gift of God’s image is indelible.

And what if, here in the 21st century, we don’t have to surrender our understanding of the cosmos to the scaffolding of Bronze Age cosmology? It is possible—urgent, even—to honor Scripture without pretending it speaks from outside history. We can cherish its witness while also holding it accountable for assumptions we no longer share: slavery, polygamy, three tiered universe, war as a sacred act, ethnic purity, apocalyptical immediacy…None of these assumptions are required for the resurrection to matter.

So what? is a fair question. If Jesus really rose from the dead, what difference does it make?

If resurrection is a divine transaction—God accepting payment in blood—then theologians must work overtime to establish continuity: a salvific through-line from then to now, a metaphysical pipeline of grace. But if resurrection is not transaction but revelation, then its power lies not in how it happened, or even when it happened because what it unveils is eternal. Been true since the before space-time. The resurrection reveals God’s grace, like God’s mercy, is eternal —“as far as the east is from the west, so far has God removed our transgressions from us” (Psalm 103:12).

We do not prove the resurrection. We do not merely receive its benefits. We participate in its vision and promise. We enact it. We work to see the world through Easter-tinted lenses to raise up again and again those things that deceit, violence, injustice, and the machinery of empire knock down.

And even if you count yourself among the skeptics, like Hitchens, this logic of resurrection—its rhythm, its defiance, its refusal to cede the final word to despair—still names something true. It’s what the atheist philosopher Albert Camus pointed toward when he wrote that the only way to deal with an unfree world is to become “so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” It’s what Alain de Botton explores in Religion for Atheists—that the sacred need not be literal to be meaningful. And it’s what even Friedrich Nietzsche, no friend of Christianity, strained toward when he wrote, “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

The Greek word for resurrection—anastasis—literally means to rise again, stand up again. And maybe that’s the point. Resurrection isn’t about escaping this world it’s about standing up in it. Again and again. Rising to meet the grief and injustice of our own Good Fridays—not with saccharine optimism, not with tidy metaphysics, not as an opiate for the masses or a reward for the righteous, or with a clinical certainty - but with stubborn, embodied hope. A hope that says love is stronger than violence. That mercy outlasts cruelty. That even when empire does its worst, even then, the story isn’t over.

Even as Rome sought to erase him, Jesus was raised up.

So what does resurrection prove? Perhaps nothing. But what does it reveal?

Everything!

In Resurrection part II I examine how different the ancient world, before Plato and Descartes, thought about the spirit (it wasn’t immaterial) and the body (which was more than just flesh). These ancient ideas are surprising but find some interesting contemporary voices.