U2’s “rockumentary,” Rattle and Hum, premiered in theaters on my birthday. My friends gave me tickets to opening night. The movie begins in darkness. You hear the crowd first—a swelling roar, electric with anticipation. Then a single sharp guitar chord slices trough the darkness. And Bono’s voice, half incantation, half indictment speaks these words,

“This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles… We’re stealing it back.

(Here is a link where you can watch U2’s Rattle and Hum in its entirety. For an 80’s throwback you can click the link and keep the audio going while you read.)

In that moment, U2 wasn’t just covering a rock song—they were reclaiming it. Helter Skelter, originally written by the Beatles as a wild, spiraling burst of sound—the title taken from a British spiral fairground slide—had been twisted into something darker. In the late 1960s, Charles Manson appropriated the song as dark prophecy, convinced it encoded a call for violence and the collapse of civilization. But Manson didn’t just misread the song, he repurposed it—imposing onto it a theology of terror. And U2 wanted to reclaim it. Not just the melody—but the meaning.

The idea of reclaiming what’s been co-opted isn’t just musical. It’s historical. Power has always excelled at twisting symbols and stripping away dignity—turning crosses into swastikas, bodies into objects, memory into silence. But like a misused lyric, history too can be taken back. Reclaimed. Re-sung in a different key.

This past weekend, in New Orleans, a different kind of reclamation took place. A funeral—150 years delayed—for nineteen souls whose remains had spent the better part of a century boxed in research collection at the University of Leipzig in Germany. They were returned home. Honored at a jazz funeral at Lawless Memorial Chapel on the campus of Dillard University. Carried through the streets in a second line procession. Buried with reverence.

To learn more about the funeral and the process of reclamation

Who were these nineteen? To answer that, we have to go back 150 years ago— Charity Hospital, New Orleans, January 1872. On a cold day that winter, a young Black laborer named William Roberts fell ill. Whatever it was—exhaustion, exposure, infection—it was serious enough that he made his way to the towering brick building on Tulane Avenue that had long served the city’s poor. The hospital record notes that he was 23, born in Georgia, and was “strong-built.” Nothing more.

We don’t know what brought him to New Orleans—whether he arrived looking for work, for safety, or for the fragile hope of a future in the fractured years after the Civil War. We don’t know what dreams he carried, what losses he bore, or what faith sustained him. We don’t know who waited for him back home. Or whether anyone ever learned what happened.

What we do know is that he died there. Alone. No family came to claim his body. No obituary was written. No funeral held. No headstone placed.

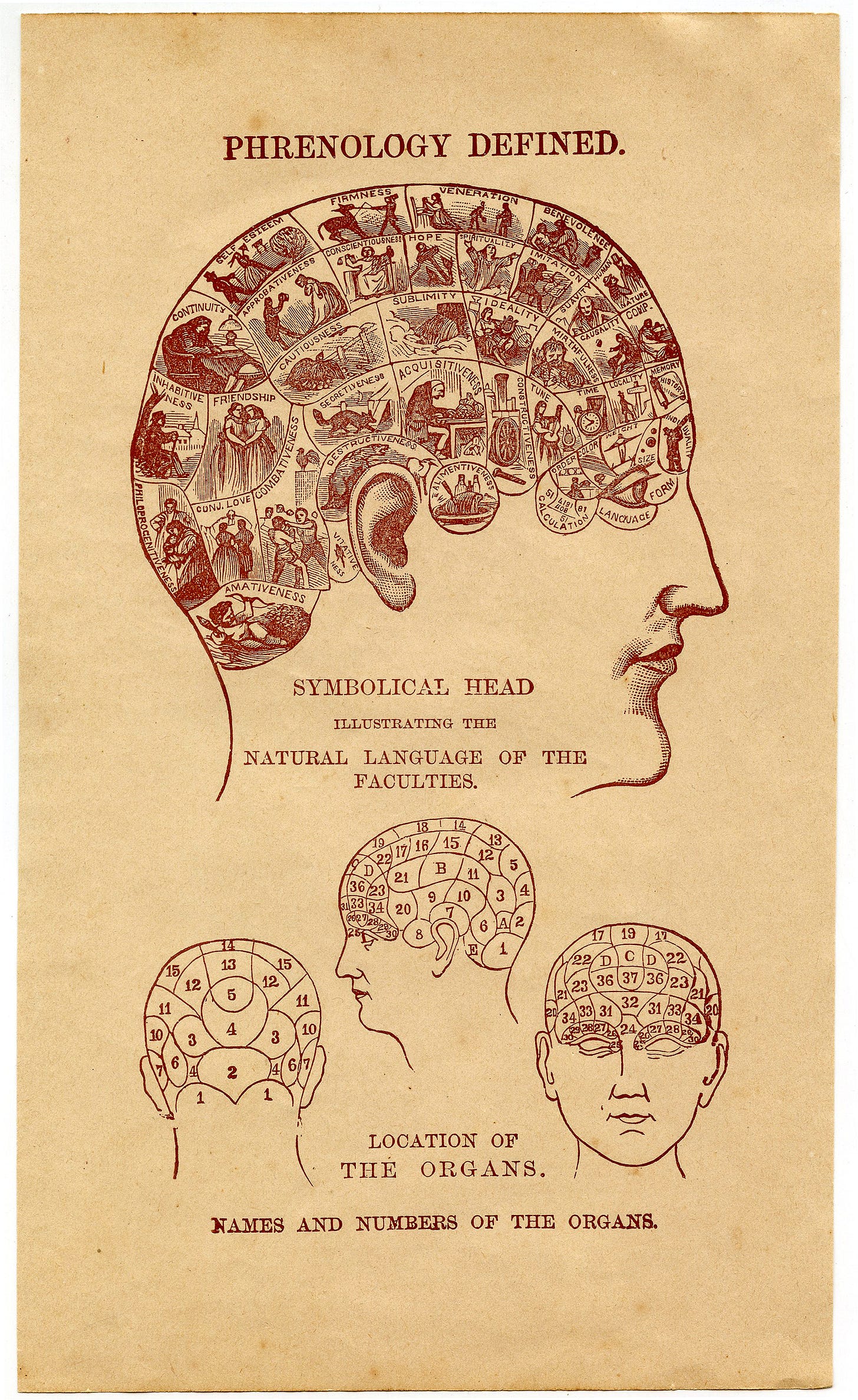

Instead, under the authority of local physician Dr. Henry D. Schmidt, his cranium was removed and sent to Leipzig, Germany. There, it was added to the personal collection of Dr. Emil Ludwig Schmidt, who had amassed over 1,300 skulls from more than forty countries—many from people of African descent— for the study of Phrenology. William’s skull became one more entry in a catalog of empire masquerading as science.

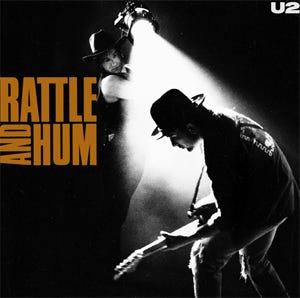

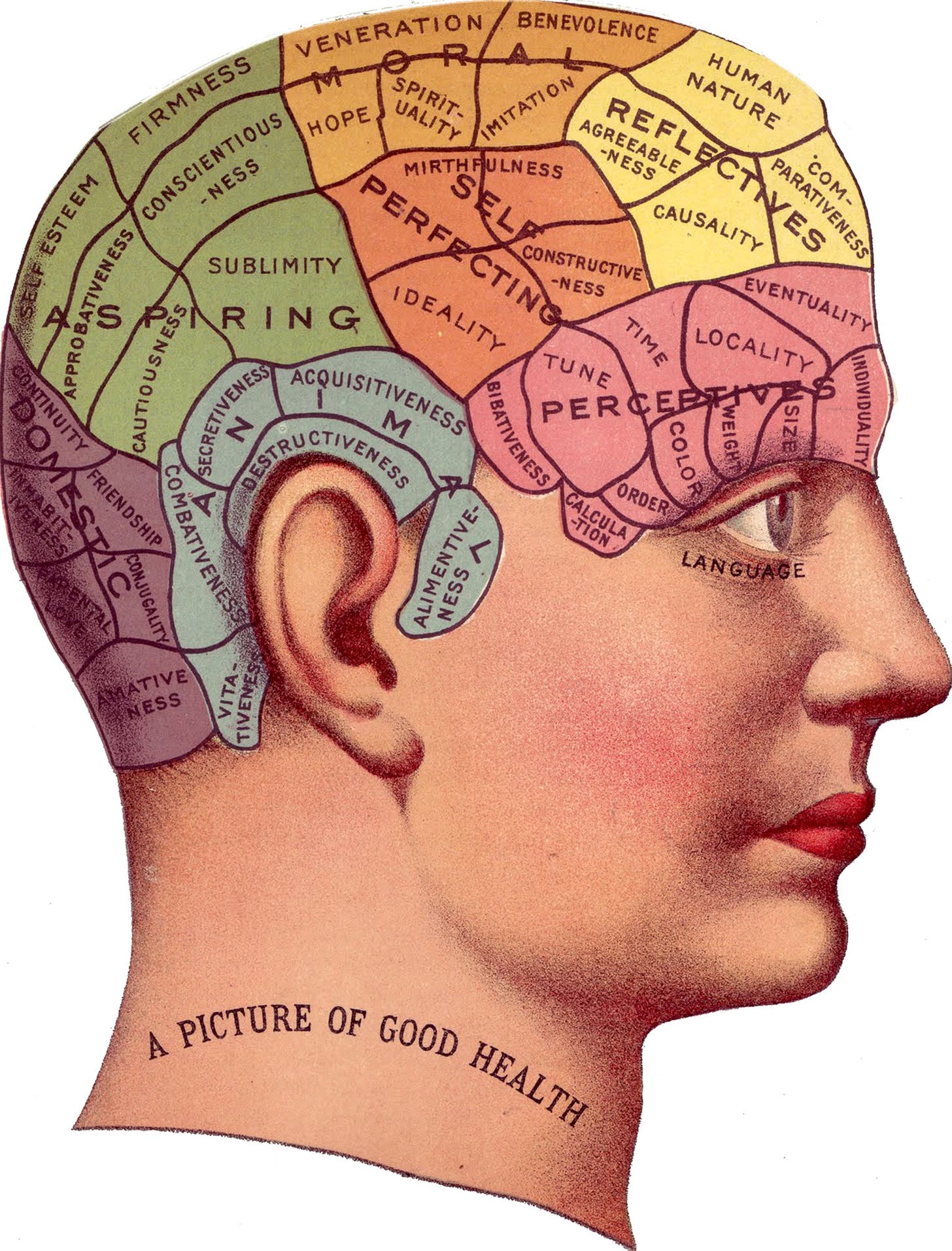

Phrenology—the 19th-century pseudoscience of cranial determinism—was gaining traction. Its practitioners believed the shape and contour of the skull revealed a person’s moral and intellectual worth. Bumps and ridges were read as signs of generosity or greed, genius or inferiority. The skull was treated as a kind of map, a divine code to be deciphered by experts. It promised to explain not just the mind, but the soul. And it gave empire what it always sought: justification. In the years that followed, nineteen other black New Orleanians were admitted to Charity Hospital. Like William Roberts, they died in obscurity and met the same fate. Their heads removed and unceremoniously shipped overseas. Studied. Measured. Displayed.

Not remembered. Not until now. The stolen crania belonged to – Adam Grant, Isaak Bell, Hiram Smith, William Pierson, Henry Williams, John Brown, Hiram Malone, William Roberts, Alice Brown, Prescilla Hatchet, Marie Louise, Mahala, Samuel Prince, John Tolman, Henry Allen, Moses Willis and Henry Anderson and two unknown and unnamed.

As someone who donated my father’s brain to scientific research, I can say—without reservation—that such studies can be sacred. There is power in science when it seeks healing and knowledge, when it honors the dignity of the one studied, when it serves life and pursues truth.

But science, like theology, is rarely neutral in the hands of humanity and never neutral in the hands of empire.

Phrenology did not remain an innocent curiosity of the laboratory. It became a tool of oppression and racism in the world. It clothed white supremacy in the garb of objectivity and science. Black and indigenous skulls were disproportionately “studied,” always found lacking, and used to argue what empire already believed: that some lives were less evolved, less moral, less human.

Of course, modern advances in neurology and psychology thoroughly discredited phrenology. The science collapsed. But the worldview it served did not. Its logic—of hierarchy, of measurable worth, of domination disguised as knowledge—had already migrated. It seeped into legal codes and zoning maps, into schoolbooks and courtrooms, into economic policy and prison design. And into sanctuaries.

That same pernicious logic animates bad theology as well. It functions like an inherited bias—rarely questioned, quietly entrenched. Once it takes root, it’s difficult to dislodge—not because it’s true, but because it becomes fluent in the language of faith. It embeds itself in our prayers, our liturgies, our assumptions about God and neighbor. And over time, it distorts the image of the divine: blessing violence, justifying exclusion, enshrining inequality, and calling it holy. It trades grace for control, mystery for mechanism, love for law.

But this wasn’t always the case. The earliest Christian communities were marked not by conformity but by confrontation. They disrupted the social order. They gathered across class lines, refused to bow to Caesar, and shared their resources in ways that undermined the economy of domination. Roman records noted them with suspicion for good reason: they looked different. They lived differently. And in a totalizing system, difference is always dangerous.

Over time, however, that dangerous difference gave way to domesticated faith. The radical unity of the early church—Jew and Greek, slave and free, male and female—was replaced by imperial theology. The church that once tore down dividing walls began building them back up.

The Most Segregated Hour

No wonder Dr. King called it “appalling that the most segregated hour of Christian America is eleven o’clock on Sunday morning.” That was more than fifty years ago. And in many places, we’ve made little progress. In some, we’ve gone backward.

King was masterful in exposing the theological architecture that undergirded segregation. He understood that racism was not just a cultural sin—it was a doctrinal one. He saw how theology, like phrenology, could be weaponized. How it often begins with a claim to truth, to divine insight, to clarity—and then quietly trades mystery for mechanism. It starts measuring worth, ranking souls, drawing maps of who belongs and who doesn’t.

Phrenology is easy to dismiss now. Its calipers and contour maps look like relics of a long-discredited past. But bad theology is harder to spot—because it is so familiar. It wraps itself in orthodoxy and tradition. It shows up in pulpits and prayer books, hides in hymnals, in liturgies and leadership. And it functions with the same imperial logic: assigning value, moral status, or salvation based not on grace, but on the theological equivalent of skull shape—gender, race, sexuality,, or the accident of where and to whom you were born.

Phrenology used calipers, measurements, and charts. Theology uses words. Words that guide our liturgies and our imaginations.

We often assume that the words we use in church are perspicuous—that they communicate clearly and effortlessly the truths we believe they contain. But after two decades of teaching in classrooms and answering questions from the pews, I can tell you this: most Christians have inherited a vocabulary of faith shaped more by empire than by Christ. The words are familiar, but their meanings have drifted—layered over by centuries of theological accretion, often detached from their original intent. Still, like a song twisted and misused, these words can be reclaimed.

I’m stealing ‘em back.

What we witnessed in New Orleans was more than a funeral. It was an act of reclamation. A taking back of what had been stolen—not just bones, but dignity. Not just names, but narratives. It was a sacred reversal of what empire and pseudoscience had tried to erase.

The remains were carried with reverence, not studied. Prayed over, not measured. Buried, not displayed. They came home. That’s what theology needs too—a homecoming.

I’ve started compiling a list—words we speak by habit, rarely question, and barely comprehend: Heaven, Holy, Repent, Sin… Even the word redemption is not beyond redemption.

Too often, theological words have been bent to serve empire. They’ve been stretched beyond recognition—pushing hope into the afterlife, privatizing salvation, shrinking grace into a ledger of debt and payment. They’ve been wielded to rationalize war, to bless conquest, to defend patriarchy, and to sanctify inequality as divine design. Language meant to liberate has been conscripted into hierarchies of control—used to decide who may lead, who is loved, who is saved, and who counts as fully human.

The deep tragedy isn’t just that theology has been coopted. It’s that many of those who have been exiled, or exiled themselves, assume that the words accurately describe God: Calculating. Fickle. Punitive. Pissed. Obsessed with eternal punishment.

Theology has been stolen - no less a theft than what was done at Charity Hospital. It removes the head and forgets the heart. It strips the story of context, relationship, grace. It’s time we freed theology and brought it home.

In the coming weeks, I’ll be writing more frequently—posting reflections that attempt, word by word, to steal back what imperial theology has taken from us. I’m starting with the language itself because what a valley of dry bones our church vocabulary has become.

When I listen to the words and images that fill our liturgies, sermons, and conversations about faith, they often feel brittle. Empty. Hollowed out. Bones devoid of breath. But language, like bodies, can be resurrected.

This is the work I’m praying for. It’s the work I’m giving myself to. And it’s the work you’re helping to carry—by reading, by sharing, by encouraging, by supporting.

Thank you!

Because I believe reclamation is possible. A song distorted can be redeemed. A body taken can be brought home. A theology hollowed out can be filled with breath again.

I aspire to be an Easter person. And so tomorrow, I’ll begin with a word we all think we know- HOLY.

The list I am thinking about is:

Holy

Resurrection

Sin

Heaven

Grace

Love

Faith

Repent

Prophet

Salvation

Doubt

Forgiveness

Thank you for your support!