21st Century Theology

An American pope. A fragile world. And a theology still shaped by empire.

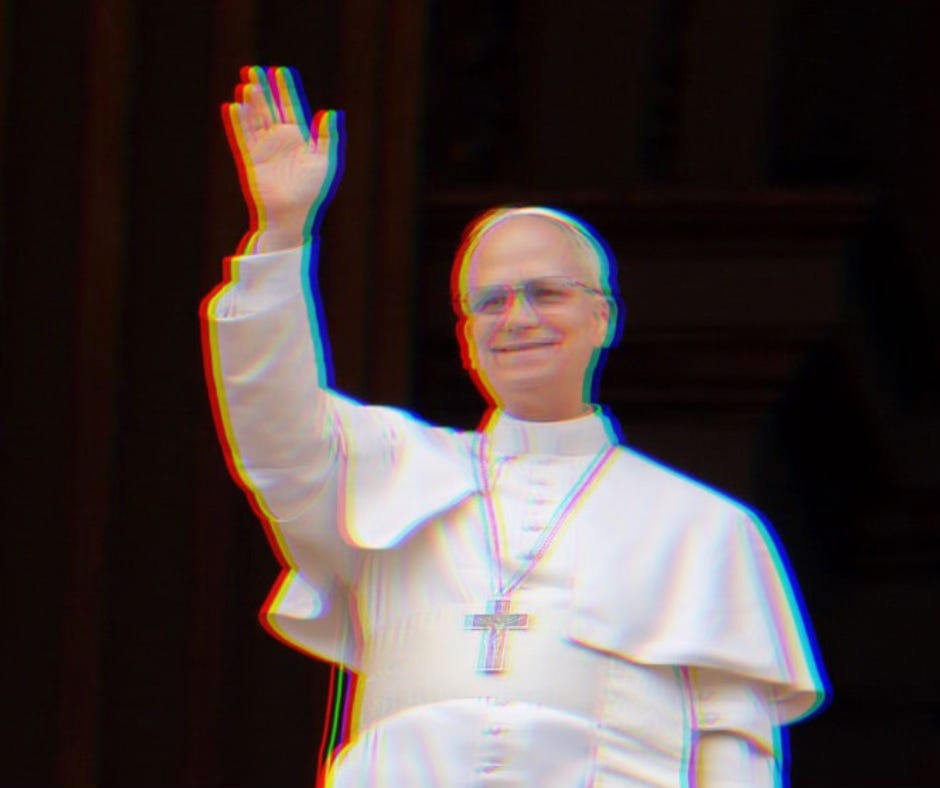

Like much of the world, I was surprised to learn that the newly elected pope, Robert Prevost, is American. For decades, it was assumed that a pope from the United States would symbolize too much American influence—too many American hands steering the levers of global politics and culture. The papacy, for all its theological weight, is also a symbol. And the image of an American bishop in white robes seated on Peter’s chair felt, to many, too much—too loaded

.And yet, here we are.

“Why Now? Why an American?”

I claim no special insight into the inner workings of the conclave—few do—but I can’t help but imagine that Rome knew exactly what it was doing. The College of Cardinals wasn’t electing one of their own in a vacuum but in full awareness of the context in which this new pope would lead. And the moment matters. Amid all the challenges facing the church—financial instability, the global sex abuse crisis, contentious debates around LGBTQ+ inclusion and women’s ordination—America, I suspect, was at the top of the list.

America is, geopolitically speaking, unmoored. Long-standing alliances that have helped sustain global peace are fraying. NATO—a post–World War II alliance built on mutual defense and collective deterrence—has been deemed dispensable. Fantastical proposals, like buying or even invading Greenland or the Panama Canal, or taunting Canada, a sovereign nation, with cooption as the “51st state” have all been floated with unsettling seriousness. Trusted allies have been mocked, while authoritarian leaders like Kim Jong-un, Vladimir Putin, and Viktor Orbán have been praised.

In a time when authoritarianism is resurgent—when borders are being redrawn by invasion and violence and democratic norms are under attack—rhetoric from a global power like the United States is never just rhetoric. When alliances like NATO are dismissed, when military escalation is casually floated, when autocrats are praised and allies mocked, it doesn’t just shift the tone. It shifts the balance. It shakes the foundations of global stability.

Words have weight—especially when they echo the very moves authoritarian regimes are making in real time. And the world has taken notice.

Robert Prevost will be known as Leo XIV (the 14th, if your Roman numerals are rusty). And his chosen name is worth pausing over.

Leo XIII, elected in 1878, was a reformer. He championed diplomacy, affirmed scientific inquiry, and reoriented the church as a moral voice for the oppressed. His 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum laid the foundation for modern Catholic social teaching, defending the rights of workers and calling for justice in the face of economic exploitation. It was a name that signaled renewal—just as Francis I had done before him.

But the name Leo also bears historic freight. Leo X presided over the height of Renaissance opulence, condemned Martin Luther, and solidified the church’s political power through lavish architecture and grandiosity. Leo IX, centuries earlier, presided over the Great Schism—a rupture with the Eastern Orthodox Church that remains unhealed to this day. The name, in other words, holds both promise in the man and peril in the weight of the institution.

And so we turn to Leo XIV.

I have every reason to believe he will follow in the steps of Francis: emphasizing humility, lifting up the poor, and continuing his decades-long advocacy for justice in Peru. But like every Christian denomination in the West, the Roman Church faces deeper, more intractable issues—issues not of scandal alone, but of theology.

I want to talk about the deepest, most unexamined layer of the church’s architecture—what I call imperial scholasticism.

Let me put it plainly: when the church goes to war—whether with the world or with itself—it still dons medieval armor and wields medieval weapons. Even Protestants don’t escape the gravity of Anselm and Aquinas. This isn’t just old doctrine—it’s a framework, a gravitational force, a way of imagining God and the world that was forged in empire and formalized through logic.

So let’s break down the overly academic name, because the concept is simple and urgent.

Imperial refers to empire—and scripture gives us no shortage of cautionary examples: Egypt, Babylon, Rome. Each claimed divine sanction. Each promised peace through domination. Each extracted wealth through oppression. And each used theology to justify their rule.

Empire, in both biblical and modern terms, is not just about kings or tyrants. It is any system that concentrates power at the top, demands allegiance and full participation from below, and justifies itself with the promise of order, prosperity, or divine blessing. Empire thrives on dominating hierarchy. It enforces control—sometimes with swords, sometimes with laws, sometimes with markets and money.

In the ancient world, empire looked like Rome. Today, it often looks like corporations, markets, or governments claiming neutrality while serving concentrated wealth. Neoliberalism is empire without a king—globalized, diffuse, and cloaked in the language of liberty. But it is still empire: it extracts, disciplines, and divides. It governs not by crown, but by capital.

Imperial theology, then, is theology shaped by these systems of power. It reflects the values of empire more than the character of Christ. It sanctifies hierarchy. It spiritualizes inequality. It defends the status quo under the banner of divine order.

If imperial describes the power structures that shaped theology, scholasticism names the intellectual system that locked it into place.

Emerging in the medieval period, scholasticism sought to organize Christian thought into logical, orderly systems. Thinkers like Anselm and Aquinas didn’t invent Christian theology—but they gave it a structure that aligned with their world: hierarchical, feudal, and legalistic. Questions became categories. Mystery became method. And salvation stopped being a story told around a table—it became a case argued in court.

What began as a pursuit of understanding became, over time, a means of management—of gatekeeping grace. Theology, once poetic, prophetic, and pastoral, became juridical, formulaic, and elite.

This is what I mean by imperial scholasticism: a theology forged in the shadow of empire and sealed in the stone of scholastic precision. It reinforced empire’s assumptions while claiming heaven’s authority. It built a vision of God that was penal instead of merciful, transactional instead of relational, privatized instead of communal.

And theology, once shaped by empire, doesn’t stay theoretical. It becomes instinct. It seeps into how we pray, how we preach, how we structure institutions and justify inequality. It shapes how people experience God, how churches imagine justice, and how sacred language gets weaponized in the halls of government and power.

That’s why, in the sections that follow, I want to examine these distortions—penal, transactional, and privatized—to explore how they took root, why they persist, and what a more faithful, more Gospel-shaped alternative might look like.

Because there is another way.

A theology rooted not in empire, but in incarnation.

A God revealed not in Caesar’s throne room, but at Jesus’ table.

A faith that doesn’t commodify grace or privatize salvation, but insists on liberation, communion, and shared life.

Penal

Let’s begin with the first distortion: the penal view of God.

In this framework, sin is not a wound to be healed or a relationship to be restored—it is a legal offense requiring punishment. God, in order to remain just, must ensure that someone pays. This vision of divine justice—codified most famously in Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo—did not arise from the teachings of Jesus or the witness of the early church. It arose from the throne rooms of feudal Europe, where justice was about honor, and honor demanded satisfaction.

In that world, a king’s dignity was sacred. Any violation of it required reparation—often in the form of blood. So when Anselm asked, “Why did God become human?” the answer followed that same cultural logic: to repay the unpayable debt humanity owed to an offended divine monarch. In this view, the cross becomes a royal blood-price paid to uphold God’s honor and payback, or balance, a debt

.

But that is not the imagination of a crucified Jew from Galilee.

That is the imagination of a medieval bishop—shaped by fealty, feudalism, vengeance, and the economics of punishment.

This doesn’t just matter to theologians it has real world consequences..

This isn’t just church talk or academic mumbo jumbo, it has real world consequences. Our current penal system is built on this theology. Without lengthy explanation, here’s the inheritance: What began with Anselm’s theory of penal substitutionary atonement was codified by Aquinas’ scholastic system, hardened by Calvin’s predetermined courtroom God, and later secularized by Enlightenment thinkers like Cesare Beccaria. His ideas on crime and punishment became foundational to modern Western justice—where retribution, not restoration, defines guilt. The American founders—Jefferson, Adams, Hamilton, Madison—absorbed these assumptions and enshrined them into law through documents like the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Penal theology trains us to see justice only as retributive. It teaches us to view the world through the lens of guilt and deservingness, where punishment becomes the currency of moral order. Over time, it becomes more than doctrine—it becomes instinct. It becomes our implicit worldview.

And though this theology may find justification in parts of Scripture, it is not the only voice—and I would argue, not the most faithful one. When Jesus referenced that very system—the lex talionis, “an eye for an eye”—he didn’t affirm it. He subverted it. He pointed to a better way: a justice grounded not in equivalence but in mercy, forgiveness, and radical reconciliation.

Transactional

The second distortion is the idea that grace is transactional—not something we earn, but something we must first activate. In this model, grace is freely given—but only after the right conditions are met. It must be triggered. Confession, belief, baptism—these become the required actions that release what God has otherwise withheld.

Forgiveness is delayed until confession. Salvation is postponed until baptism. God’s love becomes a reward—not for merit, but for compliance: repent, invite, believe, get dunked, sign here. But that’s not grace. That’s an economy of exchange. That’s how a vending machine works. And if your theology treats God like a cosmic dispenser—insert the right ritual, receive mercy—then the gospel has been reduced to a transaction

.

Certainly, many of our human relationships work this way—conditional, codified, easy to measure and control. But if grace is truly to be grace, it cannot operate on those terms. It must be free, uncoerced, and untriggered—given not because we did the right thing, but because that is simply who God is.

By contrast, a revelational model says something far more beautiful—and far more disruptive:

You are already forgiven. The love was already there. The cross didn’t purchase grace. It revealed it.

In this frame, confession isn’t a tollbooth on the road to forgiveness—it’s the moment the scales fall from your eyes (Acts 9:18). You finally see what has always been true: that you were never unloved, never forsaken, never beyond the reach of mercy. Confession isn’t the price of grace. It’s the awakening to it.

The same holds true for baptism. In a transactional paradigm, baptism is the moment salvation begins—it changes your status, alters your essence, secures your name in the divine ledger. It marks an ontological shift. But in a revelational frame, baptism doesn’t change you—it reveals what’s already true: that you are made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26–27), filled with the divine breath and Spirit (Genesis 2:7), and marked by belovedness from the very beginning—of your life (Psalm 139:13, “For you knit me together in my mother’s womb”) and of the cosmos itself (Genesis 1:31, “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good”).

Baptism, in this light, is not the start of grace—it is the unveiling of it.

And this reorders everything!

In a revelational model, grace is the starting point—not the payoff. We don’t strive to trigger it; we live in response to it. We embody it in our lives, extend it in our relationships, and advocate for it in our politics. If there’s a line that should shape your vote, it’s the one we pray nearly every time we gather as the church: “on earth as it is in heaven.”

Of course we will stumble. Of course we will turn away.

But repentance—turning back to God—isn’t the trigger for forgiveness.

It’s the reminder of what’s always been true.

A revelational model of faith opens the door wide.

When we say in the Eucharist, “The gifts of God for the people of God,” does that mean only the baptized—because the revelational model assumes that all people are made in the image and likeness of God. That reality, though we may resist or forget it, is indelible and universal.

Your presence at the table—your hands held out to receive, if Eucharist is your tradition—is not a transactional exchange. It is a recognition: that you belong here, that you bear the image of God, and that you are willing to live in the way of Christ. And that path, if followed with intention, may well lead to your baptism—not as a prerequisite for grace, but as a response to it.

I love the Augustinian invitation to communion “Behold what you are; become what you receive.” Not through a contract. Not a transaction. But through participation, together.

Participation in the image of who you already are, as opposed to all the other images and likenesses the world tries to give you—images that are, at their core, transactional.

To be a consumer. A competitor. A cog in the machine.

To put something in and get something out.

That’s the logic of empire.

But it cannot be the way we speak about ourselves in light of a loving and grace-filled God.

Privatized

The third distortion may be the most pervasive in American Christianity: the belief that salvation is private, personal, and asymmetrical—something God does for me, something Jesus accomplished for my sins, something I secure through my decision.

In this model, faith becomes a solo journey.

Salvation becomes a private possession.

Heaven becomes an individual reward for those who check the right boxes.

Amendment of life is optional.

Justice is secondary.

It’s just me and Jesus.

But the Bible doesn’t speak in such isolation.

From Genesis to Revelation, salvation is overwhelmingly communal. God doesn’t just call individuals—God calls a people. When Abraham is blessed, it is so that all the nations of the earth might be blessed through him (Genesis 12:3). We love to receive the gift—but often resist the “so that.” We forget the participation and responsibility to community that comes with blessing.

One common misreading of the Bible comes from our lack of a plural second-person pronoun in English. When we read verses like “Knock, and the door will be opened to you” (Matthew 7:7), we assume it means me. But in the original Greek, it’s plural: Knock, and the door will be opened to y’all. Y’all! All Y’all.

That changes everything.

In the communal imagination of Scripture, salvation is not a personal prize—it’s a shared reality. Healing for the whole body, not just one limb. The goal isn’t to escape the world, but to renew it. Not to hoard grace, but to become a vessel of it—for your neighbor, your enemy, your community, and the world.

Privatized faith always bends toward exclusion. It breeds moral superiority, resists accountability, and reduces discipleship to spiritual self-help. But communal faith insists that our salvation is bound up with others. It reminds us that we cannot be whole while our neighbor is hungry, or safe while our neighbor is harmed.

Scripture speaks with many voices, but one of its most consistent refrains is justice. And justice—real justice—is communal, economic, and political.

The gospel isn’t a ladder out of the world.

It’s a table set within it—where all are invited to eat, to be fed, and to feed one another.

And yet, even as the church proclaims this, our liturgy often betrays a privatized understanding of sin. Too often, we confess only personal faults—my failures, my transgressions, my brokenness. But Enriching Our Worship, a liturgical resource of the Episcopal Church, offers a hint at a broader vision. In the confession we pray:

We repent of the evil that enslaves us, the evil we have done, and the evil done on our behalf.

That last line confronts the limits of privatized theology.

What does it mean to confess evil done on our behalf?

It means acknowledging that the clothes we wear, the food we eat, the coffee we sip, may be stitched, picked, or harvested within exploitative systems. That we benefit from networks of harm, whether or not we built them. And if the gospel means only that I keep a clean sheet—while remaining indifferent to the structures I’m complicit in—then that gospel is not just insufficient. It’s irrelevant.

Once again, we must ask:

What does it mean to pray, “on earth as it is in heaven”?

A Different Kind of Church

The election of Leo XIV may signal continuity with Francis—a commitment to humility, justice, and care for the poor. But even the most reforming pope inherits structures forged in another age. Creeds, canons, catechumenates—the scaffolding of the church—bear the imprint of empire. And for all our prayers for peace and mercy, much of our theology still functions like a courtroom or a royal court.

That is the legacy of imperial scholasticism: a theology formed in the service of power, codified through medieval systems, and handed down as orthodoxy. It gave us a God who punishes, not a Christ who liberates. A salvation we must trigger, not a grace in which we invited to participate. A faith that isolates, instead of one that gathers, heals, and renews.

And yet…

In every age, the Spirit breaks through. The cross still unmasks the logic of empire. The resurrection still speaks of shared life, not private escape. And the table is still set—not with contracts, but with bread and wine.

Not for the worthy, but for the hungry. Not to reward the righteous, but to remind us who we are.

This is the work ahead of us: To name what we’ve inherited. To unlearn what empire taught us about God. To recover the dangerous memory of Jesus. To rebuild the church—not as a fortress of doctrine, but as a communion of grace, truth, and solidarity.

Because there is another way. And the world is starving for it.

Thank you for taking the time to read this essay. If you know someone who would enjoy reading this as well, please feel free to forward, subscribe, or support. -Andrew

Thank you for this. It gives historical context to much that I have intuited on my journey. Community in grace is what the Church needs, but also our society as a whole.